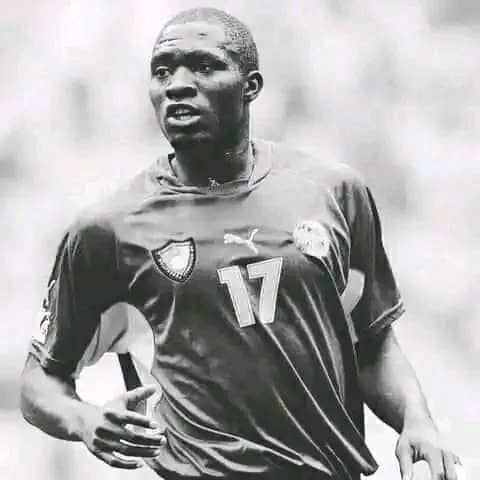

In the 73rd minute of the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup semi-final between Cameroon and Colombia at Lyon’s Stade de Gerland, powerful midfielder Marc-Vivien Foe was jogging along innocuously.

No-one was close to him and nothing seemed wrong, yet suddenly he collapsed to the ground in the centre circle. Medical and support staff attempted to resuscitate the player on the pitch, before carrying him on a stretcher to the bowels of the stadium, where attempts to restart his heart failed and the man known affectionately by his team-mates as ‘Marco’ was pronounced dead.

That was 21 years ago, on 26 June 2003, but the memories are still painfully fresh for all indomitable Lions of Cameroon fans.

A first autopsy failed to establish the cause of the 28-year-old’s death, but a second found he had been suffering from a condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The big question everyone asked was how could a fit, athletic footballer with no known history of heart problems have died in such a way? The midfielder was given a state funeral in Cameroon in July 2003.

Foe left behind a wife and sons aged six and three, as well as a daughter of only two months old. The player’s generosity had been legendary, and there were reports that he hadn’t much money left behind.

Foe was buried on the site of the football academy he had been having built in his hometown of Yaoundé. He used to send a proportion of his wages home to his father Martin each month to fund the construction of the complex, but now “sadly it has practically been abandoned now because of lack of funding”.

What happened on 26 June 2003

First, there is this terrible image of the player on the ground, eyes rolled back, shortness of breath, chest panting. There, just a few seconds ago, Marc-Vivien Foé – Marco for all – collapsed alone, without the slightest contact, on the grass of Gerland, in Lyon. Its lawn, its stadium, its city.

Aware of the situation, Mario Yepes, the Colombian central defender of FC Nantes, signals to Éric Djemba-Djemba, his teammate with the Canaries. Winfried Schäfer, the German coach of the 2002 African champions, made the change immediately. Valéry Mezague (who also died of a heart attack in France eleven years later) enters, while Foé is evacuated on a stretcher to the stadium’s medical antenna. The Indomitable Lions have been leading the mark for more than an hour, thanks to a goal from Pius N’Diefi (9th minute).

The match ended with the victory for Cameroon, synonymous to qualification for the final. But a drama played out at the same time, without supporters, viewers, friends, teammates or parents being aware of it: life ran away from Marc-Vivien Foé, at 8:20PM according to the FIFA report. The heart of the former Canon of Yaoundé player stopped beating despite resuscitation treatment. The Cameroonian players, who went up the Gerland tunnel towards the locker rooms, came across a crying Roger Milla. “Marco has passed away,” he blurted out, his voice torn with sobs. At 8:30PM, Swiss doctor Alfred Müller, official FIFA doctor delegated to Lyon for the tournament, officially announced the sad news. The locker room, already, is no more than tears and incomprehension.

Even weakened during the competition, the team’s heartbeat, its leader, had played very well. Starter during Cameroon’s first two outings in the tournament, against Brazil (1-0), then Turkey (1-0), Marco Foé left shortly after the hour mark in his last match. He was not used against the United States (0-0) in Lyon, Cameroon having already qualified for the second round. What struck out then, was his extreme physical fatigue, he who had suffered from diarrhoea and did not hide it. He was also under treatment to combat this concern. Return to Dardilly, in the Lyon suburbs, in the Foé pavilion where Marie-Louise, his wife, receives the whole group, but also Blatter and the president of the African Football Confederation (CAF), the Cameroonian Issa Hayatou. The Lions make the decision to play the final, three days after the sudden death of their friend. They return to Paris on Saturday during the day by train, and settle in Marcoussis. Among the most affected, the captain, Rigobert Song.

His brother, with whom he made his debut in 1993. Samuel Eto’o, who returned to Spain to play with Mallorca in the Copa del Rey final against Recreativo Huelva (3-0, brace by the Cameroonian striker), especially returns to Paris to be part of the match.

Sunday June 29, Stade de France. At the time of the warm-up, the entire Cameroonian team wears a training outfit embedded with the number 17.The one that Foé wore. Song holds a giant portrait of his friend. On the pitch, the Indomitable Lions are playing their luck. “We are on a mission,” Song had warned. They even keep the Blues in check until the end of regulation time. Eto’o entered after the hour mark, hope is real. But very quickly, Thierry Henry scored the golden goal during extra time (1-0, 97th minute) and offered the Confederations Cup to the French team, the second in its history. Moments later, Marcel Desailly poses alongside Song, trophy in hand, surrounded by the Blues.

Marc-Vivien Foé will finally be buried a few days later, on July 7, in Cameroon, during a national funeral. The autopsy will conclude with a natural death, due to a congenital cardiac hypertrophy.

Foé, who had turned twenty-eight at the end of May, was simplicity personified, a truly generous man. Five months later, on November 11, 2003 at the Gerland stadium, where the drama began, a match organized by former defender Basile Boli will bring together former club teammates and the Cameroonian selection. A Cameroonian proverb will therefore summarize the feeling of all: “A lion never dies, he sleeps …”

Sports Medicine Legacy

Close to two decades on, football will remember a fine player who grew up in poverty in Africa and went on to play in some of the biggest leagues in Europe.

Foe arrived at West Ham in 2000 as their club record 3 billion FCFA signing, yet could not have been more unassuming.

“He was much-heralded and seemingly had the world at his feet,” says team-mate Shaka Hislop, “but he was as genuine and likeable as they come. Regardless of what was asked of him, he did it with a smile and I thought he represented the best of football and footballers.”

Foe had been on loan at Manchester City from Lyon in the 2002-03 season, making 35 appearances and scoring nine goals. City retired his number 23 shirt after his death, while a street was named after him in Lyon.

A positive result of Foe’s death has been huge improvements in both the testing of footballers for heart problems and the treatment they receive during matches.

Fifa’s former chief medical officer, Jiri Dvorak, admits big improvements had to be made following Foe’s death.

“We have done a lot of work to reduce the risk of sudden cardiac arrest since then,” he told BBC Sport. “At all levels, we have examination of players before arrival at a competition.

“We have also trained the side-line medical teams in CPR and using defibrillators. We have a plan if something happens and the equipment – including for the team physicians of all teams.The medical personnel are adequately educated.”

Professor Sharma says such improvements were in evidence when Bolton midfielder Fabrice Muamba suffered a cardiac arrest during an FA Cup match against Tottenham in March 2012.

Foe’s legacy does have a good side too, as FIFA reacted by introducing new protocols to ensure players had quicker, and better treatment, on the rare occasions that such episodes occurred – and that may just have saved Eriksen’s life during the Euro 2020. There could not be a better way to remember Marc-Vivien Foe.

It is important to remember Miklos Feher, Cheikh Tiote, Antonio Puerta, Bafetimbi Gomis, Fabrice Muamba and recently Christian Eriksen who all had on-pitch health issues.

Denmark’s Christian Eriksen will be fitted with a heart-starting device following his collapse on the pitch during Euro 2020. The 29-year-old midfielder suffered cardiac arrest in his side’s defeat by Finland in Copenhagen on Saturday 12 June 2021.

The ICD – implantable cardioverter defibrillator – is “necessary due to rhythm disturbances”, Danish team doctor Morten Boesen said.

The British Heart Foundation describes an ICD as a small device which is placed under the skin, is connected to the heart with “thin wires” and “sends electrical pulses to regulate abnormal heart rhythms”.

Netherlands and Ajax defender Daley Blind was diagnosed with a heart condition in December 2019 and returned to action in February 2020 after having an ICD fitted. The 31-year-old is part of his country’s squad at Euro 2020 and played in their opening game, which was a 3-2 win against Ukraine.

Manchester City have jointly funded the donation of 26 defibrillators to grassroots clubs in East Manchester. And the roll-out of the lifesaving equipment has come at a poignant time, coming just days after the Christian Eriksen heart scare – and 18 years since the death of Blues midfielder Marc Vivien Foe after he collapsed on the pitch while representing his country.

Now City have put up 15 million FCFA to equip local junior clubs with automated external defibrillators (AEDs), with Manchester FA also in on the scheme, and providing training in the use of the life-saving machines.

AEDs can diagnose a cardiac arrest and treat it with an electric current to the heart and will be on hand at pitch side during matches and training for east Manchester clubs.

In Cameroon: No Legacy

Foe was flown back to Cameroon, where he was given a state funeral in the capital city of Yaoundé, with the country’s president Paul Biya in attendance.

His body was placed initially in the Ahmadou Ahidjo stadium, home to the Cameroon national team, and scene of some of his greatest triumphs, and over 30,000 fans turned up to pay their respects.

His standing in Cameroon was reflected by the fact he was given a funeral with military honours, for “defending the flag” on the football pitch rather than the battlefield.

He was declared to be a Commander of the National Order of Valour, and laid to rest in a sports complex he was helping to build in the suburb of Nkomo, and which was expected to bear his name.

But the tragedy of the Cameroon international’s death, at the age of 28, is still being felt by his family, and his community in his home country, nearly two decades later.

But what should have been a fitting and lasting legacy, the Marc Vivien Foe Sports Complex in Yaoundé, turned into a nightmare for his family and friends, as work stopped on the construction of the half-built complex.

Foe had been the main funder of the expected 2.6 billion FCFA cost of the centre, intended to give talented Cameroonian kids the chance to excel in their chosen sports – it was meant to have tennis, handball and volleyball courts as well as football pitches, a fitness centre and an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

His death saw the development grind to a halt, apart from the erection of a fibreglass statue of the man, which one devoted fan placed outside the complex, two years after his death.

One big problem was that in Cameroon, the norm was for his father to inherit Foe’s wealth, but his wife Marie-Louise, living in Europe and with a family to look after, made the case that she needed her late husband’s money – it was a culture clash rather than a squabble over the cash.

The family asked for help with continuing the work on the complex, as a fitting legacy, but to this day the place is a shell of crumbling concrete, partly over-grown – and the sports fields have been ploughed by local farmers and planted with crops.

Family members Joseph Mbende and Joseph Nkono spoke for the family and appealed for the 2.6 billion FCFA sports complex to be completed, an appeal that fell on deaf ears.

The outdoor pitches have already been converted into farmland, after a battle between Foe’s family and local farmers, and the buildings are a shell, partially overgrown.

His nephew Assiga Foe said: “We are dejected. It is tough to take, it is really sad.

“Friends are always there only when you are alive. When you are gone, everybody forgets about you. You can see the complex has been abandoned. It is really sad.”

But even worse than the sad story of what should have been his legacy is the devastating effect it had on his family.

Foe’s father suffered a stroke after his son’s death and moved to France so he could be cared for by his family, but even worse befell his son, Marc-Scott Foe.

But Marc junior not only struggled to cope with his loss, but he also felt the pressure of being expected to live up to his dad’s reputation, when he was not a talented footballer.

He fell in with a bad crowd in Lyon, and at one point his mum sent him to England in the hope he would complete his schooling and get back on the right path.

A psychologist testified that the youngster had also been struggling with pressure to “succeed his father as Cameroonian tradition”.

A French media company awards the Marc Vivien Foe Award every year since 2009 to the most promising African player in Ligue 1 – and it has been won by stars like Gervinho, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, Andre Ayew and Nicolas Pepe. The only Cameroonian to have won it is Karl Toko Ekambi, who currently plays for Olympique Lyonnais and won it in 2018 while playing for French side Angers.

The way forward

Three questions come to mind when thinking about the impact Marc Vivien Foe had on his peers and the Cameroonian public:

- Why has the state remained inactive in pursuing the Marc Vivien Foe Sports Complex whose objective was promoting multipurpose Sporting activities especially as the state has been very active in recent years in developing sports infrastructure in the country?

- Apart from a street name in the heart of the nation’s capital, Yaoundé, why is no stadium named after Marc Vivien Foe?

With all the promises made by footballers, officials, CAF and FIFA, towards Foe’s immediate family, why have these promises been left for dead such that his son was involved in a burglary? - The Cameroon Football Federation have been so dormant on Foe’s case such that there is no award, nor competition nor friendly organized in his honour even the recent double clash friendly against Nigeria. What is FECAFOOT doing so that Foe’s legacy is passed on to the next generation?

- Dulce est decorum est, pro patria mori – It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country. This Wilfred Owen quote is directed to the state of Cameroon.

Legacy is not what I did for myself. It’s what I’m doing for the next generation. This Vitor Belfort quote applies to FECAFOOT and and all other football stakeholders who assured the world that “Marco’s” legacy will live on.

Copyright©2023 kick442.com-Cameroon

All rights reserved. This material and any other digital content on this platform may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, written, or distributed in full or in part, without written permission from our management.

This site is not responsible for the content displayed by external sites